Fifty years ago, the act authorizing the Central Arizona Water Conservation Project was signed, setting in motion a project that would take 20 years to complete and would dramatically improve life in the Arizona desert. Forty years after its completion, the engineering feat still draws people from all over the globe who come to study and marvel at it.

Designed to bring 1.5 million acre-ft. of water from the Colorado River to Central and Southern Arizona annually, the Central Arizona Project (CAP) is Arizona's single largest resource for renewable water supplies. More than 5 million people, or more than 80 percent of the state's population, live in the counties — Maricopa, Pima and Pinal counties — where CAP water is delivered. The 336-mi. long system of aqueducts, tunnels, pumping plants and pipelines carries water from Lake Havasu near Parker to the southern boundary of the San Xavier Indian Reservation southwest of Tucson.

"The scope is fairly large … and there's a significant elevation change along the 336-mile route," said Tom McCann, deputy general manager. "The terminus of the project is 2,200 feet above sea level. Where we take water off the river is 400 ft. We have a series of lifts. Think about the Panama Canal, moving from one spot to another, raising or lowering the water level as you work your way across. We're kind of like that, but all uphill. We have nearly 3,000 feet of lift all together. The water is pumped up, then flows by gravity. The distance between the pumping plants varies. Some are just a handful of miles. The canal between pumping plants is designed to have a drop of six inches a mile."

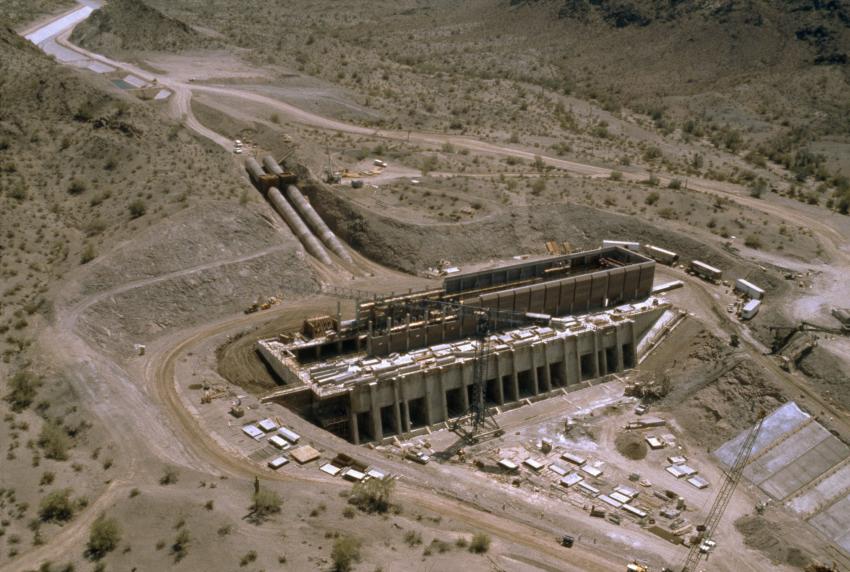

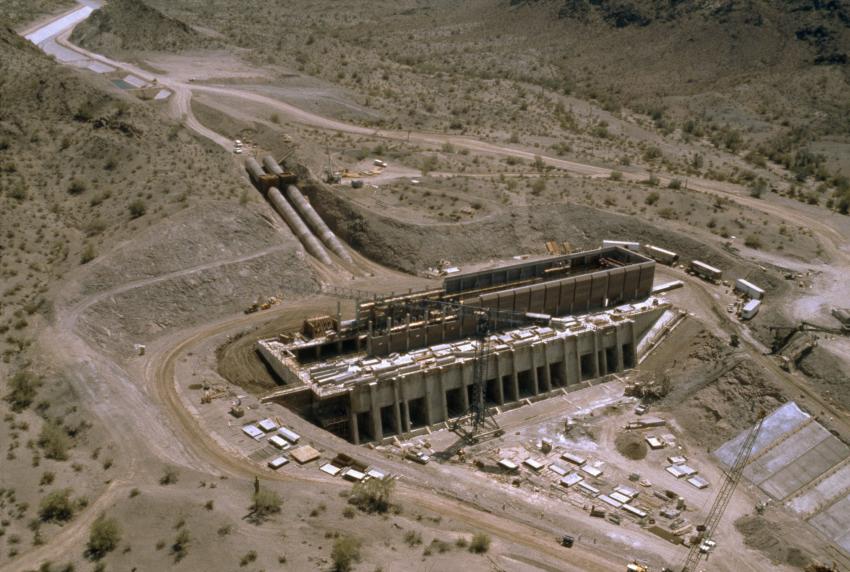

The Mark Wilmer pumping plant, named for the Phoenix attorney who successfully established Arizona's right to its allotment of Colorado River water, was the first built on the system with construction beginning in 1973. It has a lift of 824 vertical ft., and features six, 66,000 hp pumps, capable of moving 3,600 cu. ft. of water per second.

Each pump requires 50 megawatts of power, more than is required for the entire city of Lake Havasu on the hottest day of the year. When all are running, they could:

• Fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in less than three seconds

• Use the amount of energy that would be used by 300,000 homes

• Move more than 100 million gal. of water per hour

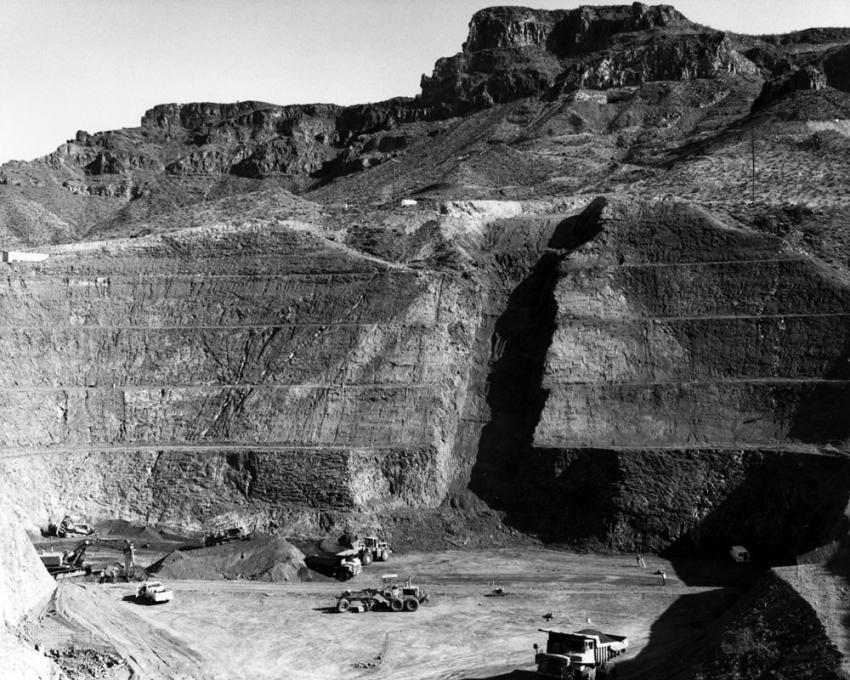

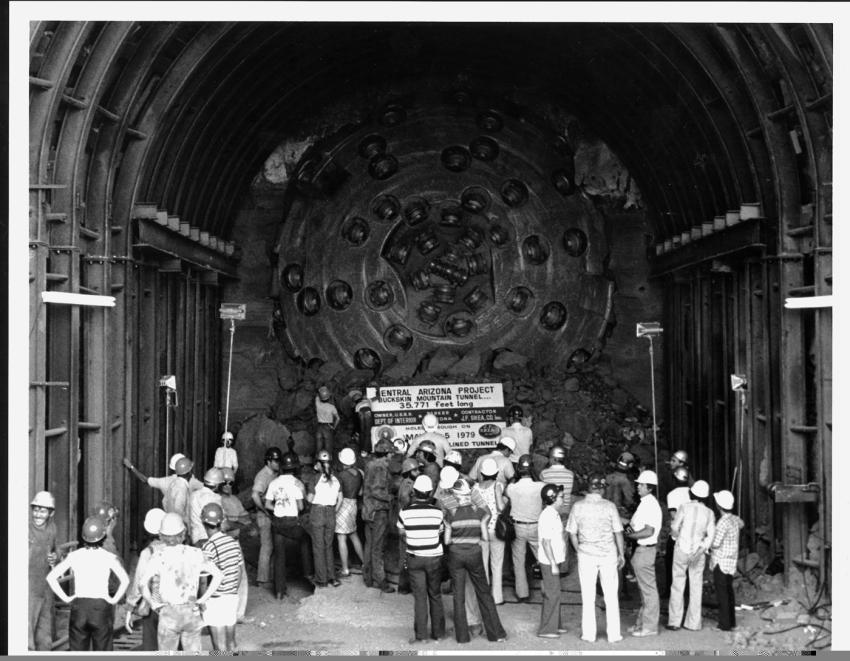

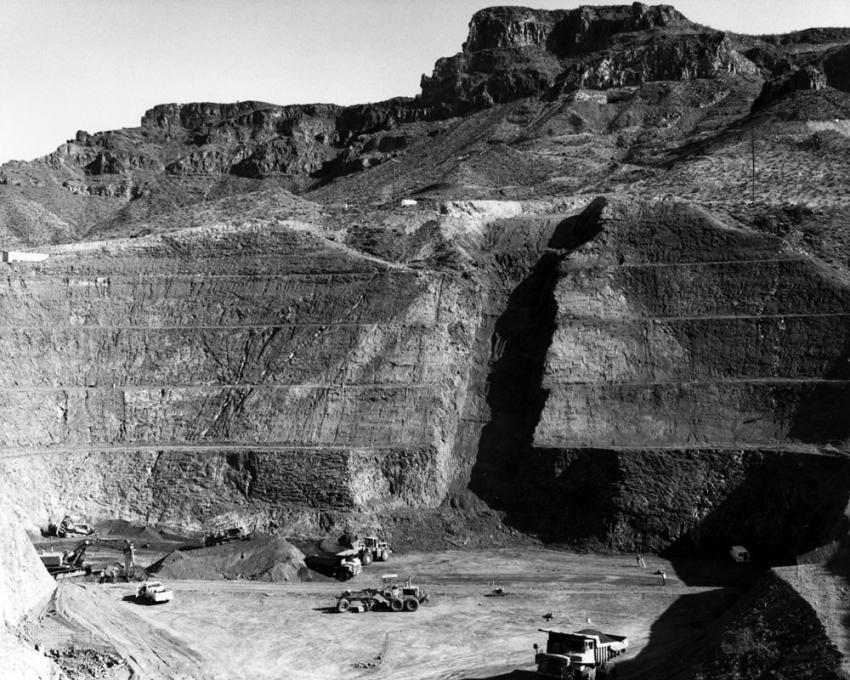

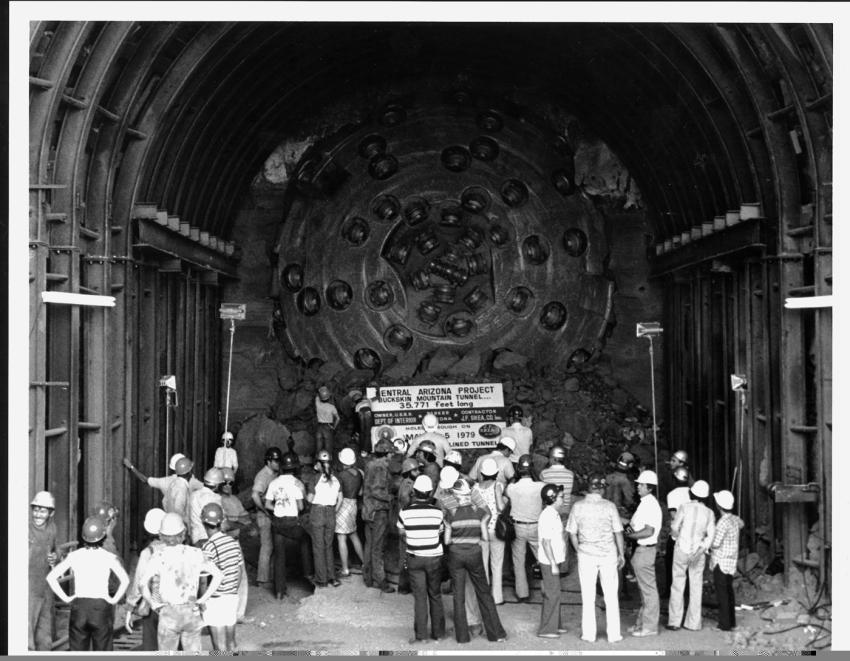

In order to move the water once it has achieved 824 vertical ft., builders had to build a tunnel to transport the water through Buckskin Mountain.

"The seven-mile long Buckskin Mountain Tunnel was quite an engineering feat. They had to know accurately where that tunnel was going to come out," said Darrin Francom, director of operations, power and engineering. "The alignment was laid out first above land and they had to figure out where it would start and end and then brought in the boring machine to build it underground.

"Another advance we saw was how they paved the tunnel. Building the canal, they first used excavators and scrapers to dig out the trapezoid. Then they had to pave the tunnel with concrete so it was better at holding water. The first sections were paved in pieces, the bottom, then the sides. But as contractors developed better technology, they pushed each other for efficiency, and paved it all at one time."

The project also used siphons 21 ft. in diameter, McCann said.

"We were moving water across the state over existing drainages that it has to cross. The way they did that was by having the CAP aqueduct flow into underground pipe and then back up on the other side. As long as you get the flow started and entry is higher than exit, the water will keep flowing through. Some of our employees have become recognized experts in prestressed concrete siphons."

Likewise, pipe used in the project also was huge.

"The pipe was the largest of its kind, calling for special fabrication to build and work with it, Francom said. "Ameron built what we call a pipe mobile. It would drive the front end of the vehicle into the pipe, grab the pipe and tilt it vertically and then is able to drive with the pipe held vertically. Put it down in place and push it home. I believe that piece of equipment was built just for that installation."

Today, CAP maintains its own machine shop on site to repair and fabricate parts and pieces of the system no longer commercially produced. The machine shop will be featured on a Discovery Channel in 2019 about ancient infrastructures.

"Some of the pieces you can't just buy, like very large butterfly valves," Francom said. "Some are 96 inches in diameter. When it's time to repair it, we bring it in and completely break it down and put it back together. Do it on pumps, wearings, bearings, bushings. The machine shop rebuilds it from scratch. Some of the equipment they use are WWII vintage. Still have the stamps in brass."

Without CAP the Phoenix/Tucson landscape would no doubt be dramatically different. The project has meant, in the shortest terms, McCann said, "life."

"The Phoenix area in particular has two primary renewable water supplies," McCann said. "The salt water project brings water off the Salt River, which starts in northern Arizona and flows down to Phoenix. That would only support growth to a certain point. At some point in the past we needed a second supply and that is what the CAP has been.

"It has really driven the economic development of the state. A study by the University of Arizona on the impact of CAP concluded that it produces about $100 billion a year. The water that CAP produces in Arizona is $2 trillion in total. About one-third of the state's domestic gross state project is directly attributable to the fact of CAP being here and making it possible to have the population and business we have."

CEG

Forty years after its completion, the engineering feat still draws people from all over the globe who come to study and marvel at it. (Central Arizona Project Photo)

CAP maintains its own machine shop on site to repair and fabricate parts and pieces of the system no longer commercially produced. The machine shop will be featured on the Discovery Channel in 2019 about ancient infrastructures. (Central Arizona Project Photo)

Fifty years ago, the act authorizing the Central Arizona Water Conservation Project was signed, setting in motion a project that would take 20 years to complete and would dramatically improve life in the Arizona desert. (Central Arizona Project Photo)

More than 5 million people, or more than 80 percent of the state’s population, live in the counties — Maricopa, Pima and Pinal counties — where CAP water is delivered. (Central Arizona Project Photo)

The 336-mi.-long system of aqueducts, tunnels, pumping plants and pipelines carries water from Lake Havasu near Parker to the southern boundary of the San Xavier Indian Reservation southwest of Tucson. (Central Arizona Project Photo)

The Mark WiImer pumping plant, named for the Phoenix attorney who successfully established Arizona’s right to its allotment of Colorado River water, was the first built on the system with construction beginning in 1973. It has a lift of 824 vertical ft., and features six 66,000-hp pumps capable of moving 3,600 cu. ft. of water per second.

The 336-mi. long system of aqueducts, tunnels, pumping plants and pipelines carries water from Lake Havasu near Parker to the southern boundary of the San Xavier Indian Reservation southwest of Tucson. (Central Arizona Project Photo)

The scope is fairly large … and there’s a significant elevation change along the 336-mi. route. The terminus of the project is 2,200 ft. above sea level. (Central Arizona Project Photo)

In order to move the water once it has achieved 824 vertical ft., builders had to build a tunnel to transport the water through Buckskin Mountain (Central Arizona Project Photo)

Lori Tobias

Lori Tobias is a career journalist, formerly on staff as the Oregon Coast reporter at The Oregonian and as a columnist and features writer at the Rocky Mountain News. She is the author of the memoir, Storm Beat - A Journalist Reports from the Oregon Coast, and the novel Wander, winner of the Nancy Pearl Literary Award in 2017. She has freelanced for numerous publications, including The New York Times, The Denver Post, Alaska Airlines in-flight, Natural Home, Spotlight Germany, Vegetarian Times and the Miami Herald. She is an avid reader, enjoys kayaking, traveling and exploring the Oregon Coast where she lives with her husband Chan and rescue pups, Gus and Lily.

Read more from Lori Tobias here.

Today's top stories