Building New York City’s Central Park in the 19th century from the ground up was a mammoth manual grading and beautifying construction project.

Editor's Note: This article is the second in an occasional series on iconic United States construction projects.)

Update: We revisit Central Park here.

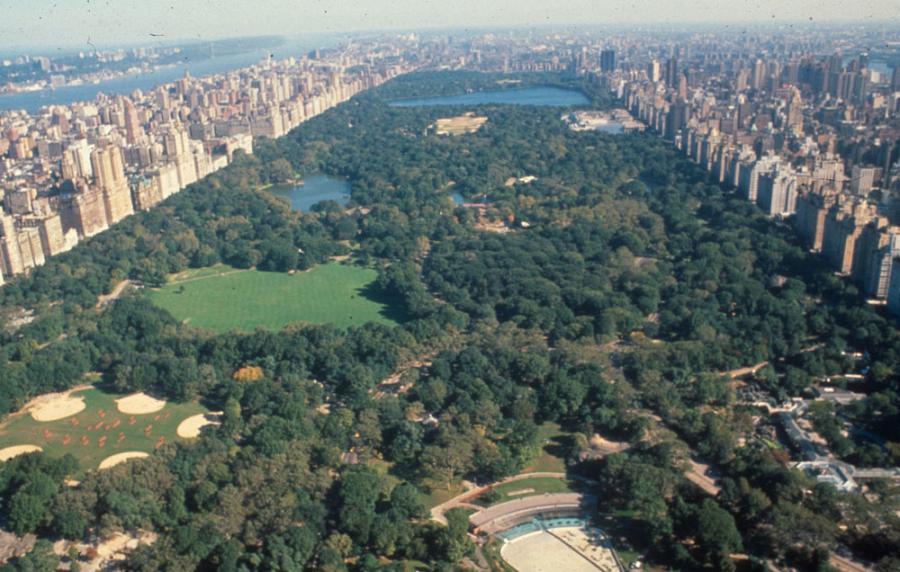

Building New York City's Central Park in the 19th century from the ground up was a mammoth manual grading and beautifying construction project that produced what many consider to be the century's greatest work of American art.

Framed by tall buildings, and changing hues with the seasons, the park is loved by many millions throughout the world.

Its construction story is an American epic, reflecting the aspirations, dreams, labors (and arguments) of generations of people who have brought this wonder into existence and have kept it alive.

Yearned for Space

The initial impetus for the park came from influential citizens dismayed by a city almost overwhelmed by teeming masses of immigrants, who were arriving at the rate of 20,000 a day in the 1840s. (The city grew from 500,000 in 1820 to 700,000 in 1850.)

Viewing the crowds, garbage and muddy streets, William Cullen Bryant, poet and editor of the New York Evening Post, urged in an editorial in 1844 that a large, new public park be built.

Andrew Jackson Downing, America's first landscape architect, kept the ball moving with an article in 1848 urging New Yorkers to develop spacious parks similar to those found in Europe.

Bryant and Downing were voicing a wide concern among the city's leaders. New York City was a leading port in world trade, and wealthy shipping magnates, for instance, were visiting London, Paris and Rome, where they enjoyed horse-drawn carriage rides through city parks.

When they got back, they saw only a few parks, like the beautiful Battery Park at the foot of Manhattan, and wondered how the city could hold its head up in the world. They also wanted the fresh air, room for promenades, and relaxing family horse-carriage rides that a new park could provide.

Almost Located on the East Side

In 1849, merchant Robert Minturn and his wife returned from a grand tour of Europe and called a meeting of business leaders at his downtown home. They decided that a park should be established at a site on the East River called Jones Wood. (Bryant also had suggested this site, a breezy 150-acre country estate near the East River between 66th and 75th streets. Owners of the property had included a tavern keeper and a smuggler.

The group had a lot of pull in the city and state, and the new park was almost built along the East River, where expensive townhouses now stand. In 1851, the state legislature authorized the city to take the land through eminent domain. When this was blocked by the courts, however, the city's Special Committee on Parks instead recommended a 700-acre central site between Fifth and Eighth avenues, from 59th to 106th streets — which has grown into today's Central Park.

A determining factor was the fact that the central area included the city's old Croton Reservoir, built in 1842, which was being augmented by a new 106-acre "upper reservoir" just above it near the center of the park area.

In 1853, the New York Legislature designated the central site for the project.

It appropriated $5 million for the land in the next three years. Approximately $1.7 million of this would come from assessing adjacent property owners. Today, Central Park's land would be worth many billions of dollars if it were on the commercial market.

Olmsted and Vaux Win Competition

A new Central Park Commission held a design competition in 1857 for design of the park, and chose a plan submitted by gentleman-farmer and journalist Frederick Law Olmsted, who had written travel books about England, and architect Calvert Vaux, an English-born protege of Andrew Downing, who had drowned before the competition trying to save other passengers in the Hudson River after the engine of a steamboat exploded on its way to New York.

Olmsted and Vaux called their design, which won a $2,000 first prize and beat out 32 other entries, the "Greensward Plan," from the English word for unbroken stretches of turf or lawn. The two men, who had only met once many years before, began a partnership that gave the country one of its greatest treasures.

Olmsted, subject to severe depression, regarded nature as a great healer. Both he and Vaux admired the new Hudson River School of American Painting and wanted the park to offer similar landscape beauty. This was no easy job.

Desolate Landscape

The land that the state had purchased was scarred and desolate. Denuded, it was a far cry from the original landscape.

"During the Revolutionary War, New York City was a British enclave; I think it was the largest British-controlled city in America," said Sarah Cedar Miller, the official historian and photographer of the Central Park Conservancy, which manages the park for the city. "During the seven years they occupied New York, the British cut down almost all the original native trees in the boroughs for building ships or for fuel."

The only native forest left in New York City is in the New York Botanical Gardens in the Bronx, mainly because a British sympathizer owned the property.

In the years since the Revolution, only second-growth trees, and not many of them, were in the projected parkland.

"The land was very rocky, with all those Manhattan Schist outcrops which of course are still throughout the park," Miller said. "It was also swampy. A lot of the soil had washed away into the many depressions throughout the area."

Approximately 1,600 working-class people also were living there. These included 270 African-Americans in a settlement called Seneca Village, which boasted a school and three churches. There also were immigrant shacks, bone-boiling plants, pig farms, at least five homes owned by wealthy citizens, and Mount St. Vincent, a Catholic convent and school owned by the Sisters of Charity, and now located in Riverdale, NY, above Manhattan.

All were evicted under eminent domain, with the residents of Seneca receiving an average of $700 per lot.

"The five homes were so nice that they kept them as park offices for the construction supervisors," Miller said.

Graded Entire Park

The construction project, which was the first urban landscape park in the United States, began in 1858, when the city had only been developed to 38th Street. Superimposing a man-made landscape, including artificial lakes, over the desolate terrain to create a park in the style of European public grounds, the job was to grade the entire park, using men and horses rather than today's earthmoving equipment.

"The park was constructed before dynamite was invented so they had to use gunpowder for the enormous amount of blasting, which went on," Miller said. "They blasted the rocky outcrops to make meadows or pathways."

Approximately 3,600 laborers, predominantly Irish-Americans who were the poor immigrant labor force at that time, were working on the park in the 1858-1860 period. An equal number were working on the new reservoir.

Most of the workers pulled carts, hauling dirt or taking it away. They earned an average of $1 to $1.50 per day. Cartmen with one horse or two horses earned a little more, as did skilled workers, such as stonemasons.

Swamplands were filled with tens of thousands of cartloads of soil. An estimated 500,000 cu. ft. (14,158 cu m) of topsoil was hauled in from New Jersey. By the time most of the park was completed in 1873, workers had handled more than 10 million cartloads of material, including soil and rocks.

"A lot of soil was carried from the upper part of the park, which had more soil, to the lower part," Miller said. "They were filling in, not excavating."

More than 4 million trees, shrubs and vines were planted to make the wasteland a beauteous retreat. Contractors were paid $30 for each tree, which lived at least three years, and nothing for failures. (The first plantings all died in their first year; today's elms were planted approximately1920.)

To produce 30 acres of slightly undulating ground for Sheep Meadow, 10 acres of boggy land had to be filled to an average depth of 2 ft. and covered with 2 ft. of topsoil. Workers blasted out protruding boulders, and reduced a rocky ridge by 16 ft. (4.9 m).

When Central Park was essentially completed in 1876, only six workers had lost their lives, which was remarkable considering the amount of gunpowder blasting.

Drained Swamps

A large portion of the park's lower area was swampland. Workers laid drainage tiles to drain much of this. Other swamp areas were filled in to make the 15-acre Sheep Meadow, the park's largest green, from 62nd Street to 79th Street.

The meadow was at one point mowed by camels from the zoo hitched to mowing machines.

Yet other water bodies became today's lakes, including the Pod, the Lake, the Loch, and the Harlem Meer, the best fishing spot in the park and one of the nation's early sport fishing lakes.

Extended to 110th Street in 1863, Central Park included 843 acres, its present total, in 1873, when its basic plan was completed as the first public park offering grand open space for the ordinary public. The huge project of building a wall around the park, completed in 1876, took another three years.

The park extends two and a half miles from 59th Street to 110th Street and is roughly a half-mi. wide, from Fifth Avenue to Central Park West.

Though it seems natural because of real grass, water, soil, trees and flowers, the park is a designed, engineered, landscape copying nature.

"Without question, this was the first time that any public park that massive had been constructed anywhere in the world," Miller said. "Most of the parks in Europe were from the aristocracy, rather than being built of the people, by the people and for the people. Central Park was truly an American innovation. Other parks in the U.S. were not built as public parks."

Lawns were created and fertilized by manure purchased from streetcar companies.

More than 100,000 people a day visited the park for ice skating in its early years. The park was "people friendly." It even had marble-and-granite drinking fountains with water piped in and running over blocks of ice.

A Children's District near 59th Street included a rustic Kinderberg — children's mountain — with chairs and tables, and also featured a dairy, petting zoo, and a lawn for cricket and the new game of baseball. One could watch a baseball game from a seat high up on a rock.

An elaborate system of arches and bridges accommodated both pedestrians and carriages.

Carriages traveled over Marble Arch, for instance, while people walked underneath it.

Total cost for the initial 20-year park-construction project is estimated at $10 million.

A Park for the Ages

Olmsted was the engineering expert on the landscaping. Vaux was the architect of the park's structures, including Bethesda Fountain, a design gem.

Luckily, their original design for meandering paths, with separate curving paths for foot, carriage and bridle paths, survived challenges from engineers proposing a straight avenue through the park, extending Fifth Avenue directly north.

When decisions were made, New Yorkers didn't waste time getting the work done. A skating pond was completed in 1858. An estimated 10,000 people thronged to it on one weekend.

Since natural scenery was to be the chief attraction, work began almost immediately on The Ramble, the rugged area around the Vista Rock between 74th Street and 79th Street, adding trees, shrubbery, a waterfall and a pond to increase its beauty and filling the low ground to the south with water to form a lake.

The Ramble was completed in June 1859.

The Mall, a formal promenade designed with Bethesda Terrace as the only straight line in the park, was begun farther to the south in 1858. A quarter-mile long, it was later compared with a cathedral because the trees that line it resemble the columns along a nave. The 150 elms along the Mall and nearby Fifth Avenue are today the two largest stands of American elms in North America, having survived Dutch elm disease in the 1930s.

Between the Ramble and Mall, Vaux designed Bethesda Terrace — named after the healing Bethesda waters in the Bible — which is considered the park's greatest architectural space.

The terrace, adjacent to a lake, conceived and created before, during and after the Civil War, is considered a masterpiece and the heart of the park. The "Angel of the Waters" Bethesda Fountain, designed by Emma Stebbins, is considered the park's spiritual center.

Drives and walks also were begun in 1858, and they were all paved in 1859.

To withstand frost heaves, workers laid rectangular foundation stones 7 in. deep, and then added a 5-in. inch layer of smaller stones. They then topped it off with 1.5 in. of finely screened gravel. The roadway was then rolled and compacted by a 6.5-ton cylinder pulled by six horses.

Laborers also built gutters and laid drain tiles along the drives.

By 1863, more than 9 mi. of carriage drives had been completed.

In 1871, Belvedere Castle, a medieval-type fortress, was built atop Vista Rock.

Olmsted and Vaux adapted their original design to new ideas, which were suggested to the park commission.

Elements, which they incorporated in their design, included the four, 8-ft. deep sunken transverse roads, which cut across the width of the park. Originally in a plan of Engineer Egbert Viele, they are considered the most important technological innovations in the park's design, and a forerunner of today's highway systems. Shrubs disguise the roads so they don't disrupt the landscape.

Park drives were state-of-the-art Telford and Macadam, far better than the city's rutted dirt roads.

The park, in fact, almost took on a life of its own. Though its designers envisaged a nature refuge, countries throughout the world donated statues and other gifts. People even started giving live animals.

"That's why the park has a zoo, which wasn't originally planned," Miller said. "At first the park received swans; then it got water buffalo from General Sherman. People gave squirrels to the zoo. I ask, 'are all these squirrels in the park escapees [from the zoo]?' Why give a squirrel or a turtle to the zoo unless it was kept at the time and your mother made you? P.T. Barnum loaned animals to the zoo from his circus."

Olmsted and Vaux were founding members of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The first building at the present site within the park was built in 1880, with Vaux as the co-designer. The west facade of the original building can be seen in the museum's Lehman Wing.

An Egyptian obelisk dating from 1450 B.C. was installed behind the museum in 1881.

Sculptures

Central Park includes more than 50 major sculptures. One of the most famous is the equestrian statue of General Sherman by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, at the main entrance to the park at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue.

The Seventh Regiment Memorial at 109th Street, showing a standing Union soldier holding a musket, influenced Civil War memorials throughout the land.

And then there is the statue of Balto, the dog that delivered serum to Nome, AK, over the Iditarod in record time, and Hans Christian Anderson, and Alice in Wonderland, and Daniel Webster, plus many others. The park has kept growing and improving.

Ups and Downs

Central Park has had its ups and downs through the years, perhaps hitting its nadir in the 1960s.

The Croton Reservoir was drained in 1931, becoming the Great Lawn, which has been the site of many concerts and rallies.

"The environmental movement, which began in the 1960s and 1970s, brought back an appreciation of nature and fear that the planet was being destroyed," Miller said. "People became interested in restoring urban parks, and we're still in that mode. I think Central Park is now appreciated as the greatest work of American art of the Nineteenth Century. Landscape architecture is an art form in itself."

Central Park now includes more than 26,000 trees more than 6 in. in diameter, and approximately an equal amount of smaller trees.

The Central Park Conservancy, founded in 1980, is a private non-profit organization that is responsible for the park's maintenance and operation under a contract with the city. Its mission is to restore, manage and preserve the park.

Miller is the author and photographer of "Central Park, An American Masterpiece," which explains the design of the park and its treasures.

A native of Massachusetts, Miller worked on the book for 10 years.

"I wanted to give back to Central Park something which it had given to me," she said.

"It changed my life and made me appreciate all kinds of things from nature while I worked with an incredible group of people in restoring this masterpiece."

Further information is available on www.centralparknyc.org. CEG

Pete Sigmund

Pete Sigmund was a longtime editorial consultant and journalist of Construction Equipment Guide for which he wrote incisive, biweekly news articles and features for more than three decades. Mr. Sigmund authored many standout features for Construction Equipment Guide.

Read more from Pete Sigmund here.

Today's top stories